Por Flavio Felice

Fuente: American Enterprise Institute

17 de enero de 2019

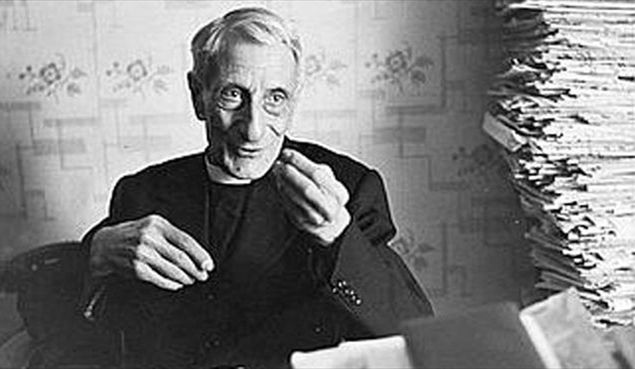

Italian historian Federico Chabod stated that the foundation of the Popular Party (PP) by Luigi Sturzo was “an extremely important event, the most notable event in the history of the Twentieth Century.” And it was historian, journalist, and politician, Giovanni Spadolini, who saw “an authentic revolution” in the non-denominational and secular nature of Sturzo’s political project: “The clean cut between clericalism and social Catholicism, the almost proud claim – by a priest – of the autonomy of Catholics in the spheres of civil life.”

Sturzo’s journey to found the PP on January 18, 1919, with a handful of friends at the Sant Chiara hotel began at least fifteen years earlier, with his historic speech at Caltagirone on December 24, 1905. On that occasion, Sturzo expressed his intention to give life to a party that had a national spirit with Christian inspiration, but was at the same time non-denominational, secular and autonomous from the ecclesiastical hierarchies. For this reason, the party that Sturzo conceptualized would not use the adjective “Catholic.” The non-confessionalism of Sturzo’s project refused at the root every temptation to make his party the “secular arm” of the religious hierarchies, and also rejected any claim to represent the unity of the Italian Catholics.

On January 18, 1919, the idea expressed in his 1905 speech became a reality. The Popular Party was born, and it was neither the “Catholic party” nor the “party of all Catholics,” but the party of “All Free and Strong Men”- the title of his Appeal-Manifesto. From a theoretical point of view, Italian historian Eugenio Guccione reminds us that the foundation of the PP represented both the arrival of Sturzo’s youthful commitment and the starting point of his maturity.

The “Appeal” followed a twelve-point program. The domestic policy priorities included the promotion of family integrity, the women’s vote, child care and protection, and the implementation of social policy based on cooperation, tax reform, land reform, administrative decentralization, and freedom in teaching. On the foreign policy front, the PP program was openly internationalist, accepting the “Fourteen Points” of Wilson and declaring itself in favor of joining the League of Nations.

The theoretical legacy of Sturzo’s political action is entirely contained in the term “popularism,” a term that opposes “populism” by virtue of the notion of “people” articulated and differentiated within it – an idea of “people” far from homogeneous and compact. This idea is refractory both to paternalism and to “charismatic leaderism” that entrust a “good shepherd” with the destinies of the flock. The founder of the PP intended to challenge with this political theory two ideological monopolies: that of the “centralizing state,” typical of the feudal Italian tradition, and that of the Marxist and socialist in the workers’ sphere. Sturzian “popularism” sought to fight against these monopolies in the field of teaching, local administration, political and trade union representation and, not least, through the spread of property and of small and medium-sized enterprises.

This theoretical approach further matured during Sturzo’s twenty-two years of exile in Great Britain (1924-1940) and the United States (1940-1946), a penalty suffered for challenging the fascist regime in the name of the “method of freedom.” This led Sturzo to lay out “popularism” in a series of markedly classical liberal policies: federalism, free schooling, liberalization, and profound Europeanism. It is precisely on the European front that Sturzo’s ideas– anti-fascist, anti-communist, and anti-Soviet– have been gathered by the founding fathers of European integration. Just as nations have been formed in modernity, passing from local units such as cities, counties, and provinces to higher territorial units, such as kingdoms and then “states,” Sturzo believed that the same evolution happened, in a federalist sense, from nations to international groups and from continental groups to intercontinental groups, respecting the principle of subsidiarity.

In the hundred years since Sturzo unveiled his vision, we have made significant progress, yet there is still work to be done. Sturzo’s idea of social and institutional pluralism, irreducible to the typical monism of the modern state, and his testimony against the totalitarian virus in every form serve as a warning in our time, and can help inspire us to commit ourselves to the daily implementation of the freedom of all, Italians and foreigners, the fate of each man.

Deja tu comentario