Por Samuel Gregg

Fuente: Religion & Liberty Online

5 de octubre de 2023

Is there a way to balance economic growth and sound environmental stewardship? If only Pope Francis would take his own advice.

If there is anything we have learned about Pope Francis’ commentaries on issues ranging from economics to the environment, it is that they invariably add up to a by-now predictable mixture.

Parts of this mélange consist of often profound insights and wisdom. But it also reflects straw man arguments, the random assembling of pieces of data plucked out of the plethora of studies available on a given subject (which smacks of cherry-picking), outright contradictions, and, alas, occasional snarky remarks directed at unnamed groups against whom the pope or whoever drafts these texts seems to harbor resentments. This usually goes together with the occasional Gospel reflection, reference to a saint or two, and a few theological remarks added almost as an afterthought, as if to remind people that the pope is actually a religious leader rather than the CEO of just another NGO.

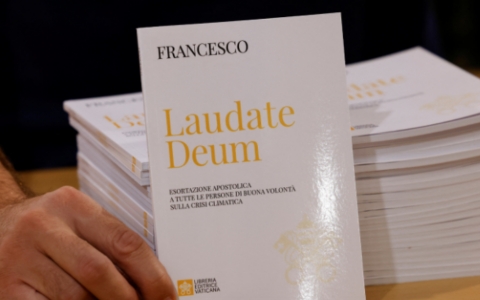

Unfortunately, the latest such papal commentary, the Apostolic Exhortation Laudate Deum, fits this pattern. Minus the first paragraph, a few paragraphs toward the end, two mentions of Francis of Assisi, and a grand total of three references to Jesus Christ in a just over 7,000-word English-language text, the document would easily pass for something produced by a secular environmentalist group making a presentation to a congressional subcommittee.

These documents often make significant contributions to public reflection on such complicated topics as how to address the nexus between economic growth that takes people out of poverty and genuine environmental concerns. Literally thousands of such texts, however, have been written and presented to countless audiences over the past 40 years. What, as an economist might ask, is the “value-add” that a religious leader might bring to this discussion?

When a religious leader writes on a topic like the environment, one might presume that the focus would be on the unique contribution that a given faith tradition could make to such discussions. Judaism and Christianity, for example, have very rich histories of thinking through humanity’s relationship to the natural world.

No such luck with Laudate Deum. There is minimal theological reflection in the text. Instead, wide portions of the exhortation consist of the pope claiming, on the basis of pieces of scientific data assembled from different sources produced by organizations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), that the world is approaching a point of no return vis-à-vis climate change. There’s little question that part of the object of the exercise is to rebuke anyone who suggests—based on other sources and analyses of data produced by perfectly reputable scientists—that things might not be quite as clear, as awful, or as definitive as your average Western European middle-class Net Zero activist gluing herself to the Pantheon claims them to be.

Plainly, Pope Francis—and whoever is advising him on such topics—believes that he needs to insist that there is an irrefutable and unchangeable consensus on such matters. In other words, people must get on board, a point unfortunately underscored by a regrettable tone of mild contempt that permeates the exhortation’s language about those unnamed individuals, groups, and “economic interests” that, apparently, are not on board.

But here’s the real problem: the pope qua pope (and, more generally, religious leaders qua religious leaders) is not qualified to intervene in the scientific dimension of these debates.

There is nothing in the particular charisma that Catholics believe the successor of St. Peter has been given by Christ that qualifies any pope qua pope to make judgments about the respective scientific claims being assembled on either side of the climate change debate. Put bluntly, the pope’s opinions about the science of climate change carry no more weight with Catholics or anyone else than mine do.

Even then, the exhortation doesn’t quite get straight a few facts that it cites—perhaps because whoever drafted the text got a little carried away in their anti-Americanism—while omitting others relevant to the discussion. For example, in paragraph 72, the exhortation states:

If we consider that emissions per individual in the United States are about two times greater than those of individuals living in China, and about seven times greater than the average of the poorest countries, [44] we can state that a broad change in the irresponsible lifestyle connected with the Western model would have a significant long-term impact [emphasis mine].

But when you look at the cited UN report (p. XVII), it says this:

Per capita emissions vary greatly across countries (figure ES.1). World average per capita GHG emissions (including LULUCF) were 6.3 tons of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) in 2020. The United States of America remains far above this level at 14 tCO2e, followed by 13 tCO2e in the Russian Federation, 9.7 tCO2e in China, about 7.5 tCO2e in Brazil and Indonesia, and 7.2 tCO2e in the European Union. India remains far below the world average at 2.4 tCO2e. On average, least developed countries emit 2.3 tCO2e per capita annually.

The United States at 14 and China at 9.7 translates into approximately 43% greater per capita emissions in America compared to China—not “about two times greater.”

Some might suggest that it’s a minor error. Fair enough. But the pope has been ill-served by whoever worked this clumsy handling of data into Laudate Deum. Moreover, a fuller picture would have involved Laudate Deum mentioning that the same UN report on the very same page (p. XVII) also lists China as the biggest emitter of Total GHG Emissions in 2020. Yet China does not get called out for this. Why?

Then there are some notable contradictions in the text. In one section, Pope Francis inveighs against the technocratic mentality that reduces our grasp of the world’s problems to technology and economics. To this I can only say: “Amen, Holy Father.” If there is anything that the response to the COVID pandemic should have taught us, it is the folly of governments effectively outsourcing policy decisions to technocrats—in the pandemic’s case to medical officials and disease-control experts who, it turns out, operated on the basis of research that proved to be highly provisional and often speculative, and in many instances was retrospectively shown to be incorrect.

The input of experts matters. But by definition, such information is highly specialized. It also needs to be integrated into the many trade-offs and, above all, ethical considerations that political leaders and governments are obliged to think about when they make decisions. As the adage goes, just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should do it. That’s the pope’s core point, and it is one firmly rooted in natural law reasoning and the Catholic faith.

But having criticized technocratic paradigms, the pope goes on to effectively propose a different version of technocracy as the way to address climate change. In paragraph 35, he states:

We are speaking above all of “more effective world organizations, equipped with the power to provide for the global common good, the elimination of hunger and poverty and the sure defense of fundamental human rights.” The issue is that they must be endowed with real authority, in such a way as to “provide for” the attainment of certain essential goals. In this way, there could come about a multilateralism that is not dependent on changing political conditions or the interests of a certain few, and possesses a stable efficacy.

Taken together, this adds up to handing over power to decidedly top-down-orientated global organizations insulated from pressures from below, and that, historically speaking, generally turn out to be very susceptible to the interests of a few rather than the many.

The World Health Organization’s embarrassing subservience to Communist China during the pandemic is a good example. As for already-existing global organizations whose official focus is human rights, consider that the current membership of the United Nations Human Rights Council includes countries with long-standing and systematic records of human rights abuse, like China and Cuba, and others like Pakistan and Ivory Coast whose human rights records are abysmal.

Much more could be said about Laudate Deum. One general point worth highlighting is that the exhortation reflects an ongoing deterioration in Catholic Social Teaching. As I and others have argued, official Catholic Social Teaching continues “to muddle the teaching of doctrine with extensive commentary of facts and probabilities that are contingent, variable, and up for legitimate debate among Catholics”; fails “to underscore the importance of understanding how the negative and positive norms of Catholic moral teaching apply when addressing social, political, and economic issues”; and downplays “the room for legitimate disagreement among lay Catholics about most [social, political, and economic] questions.”

Nota bene: these are not problems exclusive to Pope Francis’ contributions to Catholic Social Teaching. It can also be found, to varying degrees, in some of Benedict XVI’s and John Paul II’s contributions.

But let me end with a word of praise that is also a suggestion. In many ways, Laudate Deum’s most powerful statement is its very last sentence. Here Pope Francis writes, “For when human beings claim to take God’s place, they become their own worst enemies” (LD 73).

That is undoubtedly true. The validity of that claim is more than proven by the 20th century’s sad history and the behavior of regimes that disdained revealed religion, peddled ideologies that deified race or class, and ended up slaughtering millions of people. Here Pope Francis is echoing a point made on numerous occasions by Benedict XVI and John Paul II. It was given particular attention by the 20th-century French Catholic theologian Henri de Lubac, S.J., (greatly admired by all three popes) in his important book The Drama of Atheist Humanism (1944).

I’d suggest, however, that this observation—so central to the modern world’s problems—ought to be a major starting point for modern Catholic Social Teaching on our environmental challenges, rather than a concluding add-on. Much of the modern environmental movement, for example, embodies this forgetfulness of God. You don’t have to probe very far into parts of deep green ecological thought to discover the neo-pagan nature worship and outright contempt for humans that often lie just beneath the surface. Why, I ask myself, do not more Catholic bishops speak about this? What are they afraid of?

No doubt, the Catholic Church and the world will continue to wrestle with promoting the economic growth that remains the primary way to diminish poverty in lasting ways while ensuring that due attention is given to genuine environment concerns. But if there is anything that Laudate Deum demonstrates, it is that the Church needs to rethink its entire approach to this topic so it can make a distinct contribution to such discussions that draws deeply on the Catholic and natural law traditions. Pope Francis himself has said that the Church is not an NGO, and rightly warned against the temptation to become nothing more than “a compassionate NGO.” That being the case, it should refrain from speaking or acting like one.

Deja tu comentario